Coursera’s machine learning course week three (logistic regression)

27 Jul 2015This is the second of a series of posts where I attempt to implement the exercises in Stanford’s machine learning course in Python. Last week I started with linear regression and gradient descent. This week (week three) we learned about how to apply a classification algorithm called logistic regression to machine learning problems. We’re still on supervised learning here, as we still need a training set of data before we can run our algorithm. As before, here is the ipython notebook of my code.

Disclaimer: I am still learning this material, so there could be inaccuracies in the following explanation/code. I recommend if you’re learning this for the first time yourself that you also do your own research! Also, if you spot a mistake, I’d really appreciate it if you send me an email. :D

Logistic regression is a confusing name

Here’s a thing that’s confusing: when I hear ‘regression’, I think of a model that is used to predict continuous response variables (as we were last week with predicting the profits of food trucks in various cities). However, in a machine learning context logistic regression is commonly used as a classification algorithm. A classification algorithm is used to assign data into discrete categories, for example filtering our emails into spam or not spam, or diagnosing a tumour as malignant or benign. In its simplest form, we are considering just one outcome, which can be one of two states (e.g. is this email spam or ham?); this is called binary classification. Why then is this called logistic regression and not logistic classification? Fundamentally, the continuous variable that we are modelling with logistic regression in this context is the probability that our new input belongs to a particular class. Logistic regression only becomes a classification algorithm when we also decide on a probability threshold for assignment into one category or another (more on this later). In fact, logistic regression wasn’t even developed for this purpose, and is still widely used for things other than classification problems.

Why not use linear regression?

Ok, but why this function? Couldn’t we just choose to model the probability that our input belongs to a particular class (let’s call this p(x)) linearly with respect to x? For example, if we were classifying tumours into malignant or benign based on volume, we could just decide that for every increment of increase in volume, the tumour is incrementally more likely to be malignant, and vice versa. Why get fancy about it?

Part of the reason that we don’t do this is that the logistic function (the function that we use in logistic regression to model probabilities, otherwise known as the sigmoid function) is better-suited to modelling probabilities than linear regression is. The logistic function is defined as:

which when plotted on a graph, looks like this:

What you’ll notice is that the logistic function, for any given input variable (on the x axis), only varies between 0 and 1 (on the y axis). If you were to extend these axis to \(-\infty\) and \(+\infty\) you would see that the line would continue to tend towards 0 and 1 on the y axis, respectively, but never reach them. This is very useful for describing probability, since the probability that an event can occur will never be greater than 1 or less than 0. If we were using a linear function, we would be able to get values greater than 1 and less than 0, which doesn’t make sense in probability terms.

Another reason to use the logistic function is that it nicely captures how changes in the input variable(s) over certain ranges have more influence on the probability (y axis) than over others. To use the tumour example again, it’s probably not true that if we keep doubling the size of the tumour, it’s going to be twice as likely to be malignant as it was before. After a certain point, a large tumour is highly likely to be malignant, and further increases in size won’t change the probability much. However, there’s going to be a middling range of tumour sizes over which a doubling of volume will have a big influence on the likelihood of malignancy. The logistic function shows this in the steep section in the middle of the curve.

If you want a fuller background explanation into why logistic regression is used for classification problems, I found this to be useful. (Note: one of the reasons is ‘tradition’.)

Week three programming assignment: logistic regression

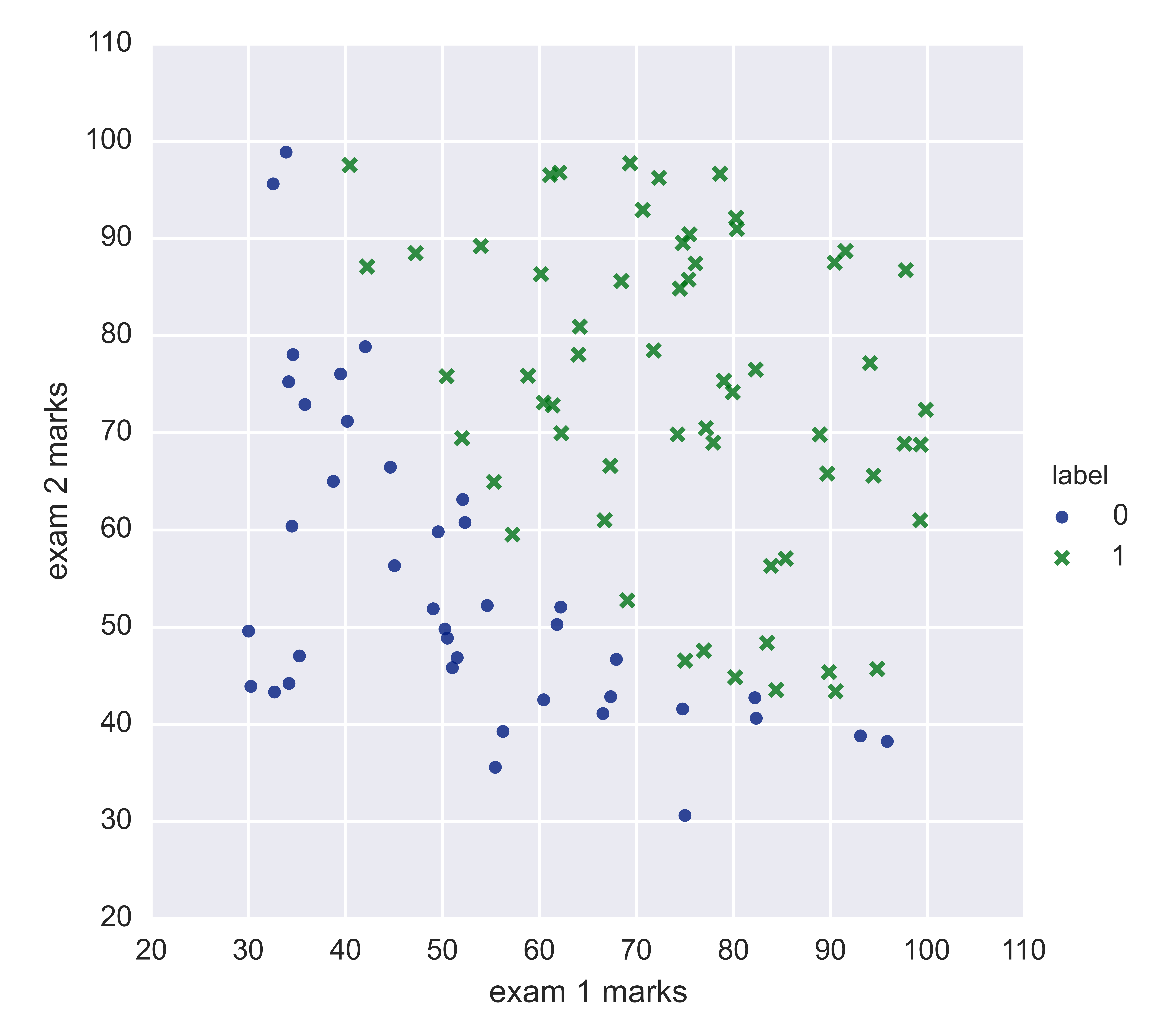

The first problem in this week’s programming assignment was about student admittance to university. Given two exam scores for students, we were tasked with predicting whether a given student got into a particular university or not. We have access to admissions data from previous years (which will form our training set). Here’s a scatter graph of the training data, with students that were admitted represented by green crosses, and with students that didn’t get admitted represented by blue circles:

You can see a curve of where the boundary for admittance lies. We want to model where this boundary is and use it to predict the admissions success of future hopefuls.

Hypothesis generation: the sigmoid function

You may recall from my last post that a hypothesis in machine learning refers to an output from our machine learning algorithm. We represent the logistic regression hypothesis mathematically as:

So the hypothesis function for logistic regression looks like an extension of the hypothesis function for linear regression, which was simply \(h_\theta(x) = \theta^Tx\). You can think of the \(g\) function as a wrapper that implements the logistic function:

so in combination, the hypothesis function for logistic regression looks like this:

How do we interpret the outputs of this function? In the context of logistic regression, our hypotheses refer to the probabilities that our inputs belong to a particular class. So, in this example if we have a student’s exam results for both exam 1 and exam 2 (corresponding to features X1 and X2 in our training set), our hypothesis function will return the probability that y = 1, which is the probability that this student will be admitted to university. Since this is binary classification, the probability that the same student won’t be admitted is simply 1 minus this value. This statement can be otherwise be represented as:

which we read as ‘the probability that y = 1, given features x, parameterised by theta’ .

Here’s how I implemented the sigmoid function in Python:

1

2

3

4

def sigmoid(z):

g = np.array([z]).flatten()

g = 1/(1+(np.e**-g))

return g

Our input z can be a scalar value or a matrix. The aim of our machine learning algorithm is to help us to choose parameters for \(\theta\).

###The cost function for logistic regression

In the last post, I explained how we need a cost function so that we can quantify how accurate our machine learning hypotheses are with respect to the real data. For logistic regression, we use a cost function to tell us what penalty should our learning algorithm pay if the hypothesis is \(h_\theta\) (remember, these are the predicted probabilities for each student that our machine learning algorithm gives us) and the real value is \(y\) (1 or 0 for if a student is admitted or not). Mathematically, the logistic regression cost function is:

This looks complex, but let’s break it down. The terms on the left of the equals sign simply mean ‘the cost of the output with respect to the actual values y’ . The terms to the right of the equals sign will compute differently, depending on whether or . If , will cancel out to zero, just leaving . On the other hand, if , will equal zero, so you’re just left with . What’s good about this cost function is that if both and , the cost will be zero (because ). Similarly, if both and are zero, then the cost will also be zero (because again. However, if and and vice versa, the cost will be very high, because tends towards . So if our algorithm predicts an outcome with such certainty, and it turns out to be wrong, the penalty will be extremely high. Here’s how I implemented the cost function (denoted by the letter J) for logistic regression in Python:

1

2

3

4

5

def costJ(theta, X, y):

m = len(y)

hypothesis = sigmoid(X.dot(theta).T)

J = -np.sum(y*np.log(hypothesis)+(1-y)*log(1-hypothesis))/m

return J

Now if we feed the cost function values for a vector of parameters (\(\theta\)), our feature matrix (\(X\)), and our vector of actual admissions (\(y\)), we can calculate the cost of this hypothesis. If our initial \(\theta\) is set to a vector of zeros, you can see in the ipython notebook that the cost is about 0.693.

The learning algorithm

So far, we haven’t actually done any machine learning. But if we want to find the values of the parameter that minimise the cost function, we need to use a machine learning algorithm to do this. Last week, we coded our own function to implement the gradient descent algorithm. However, outside of a machine learning course, it’s very unlikely that we’d sit down and code our own optimisation algorithms; in fact it’s a bad idea unless you really know what you’re doing. There are other optimisation algorithms that are more sophisticated and more scalable than gradient descent, but which are more tricky to understand, let alone code ourselves. Fortunately, there’s about a bazillion optimisation algorithms available pre-prepared for Python in the Scipy library. This week, we were told to use the fminunc function in MatLab. fminunc finds the minimum of an unconstrained multivariate function (unconstrained means that the input to the function we are trying to minimise can take on any value). According to this, fminunc is a version of the BFGS algorithm.

The scipy equivalent of BFGS is Scipy.optimize.fmin_bfgs. I’ll start by showing you what the fmin_bfgs function looks like in python:

1

2

3

4

5

6

Result = sp.optimize.fmin_bfgs(

f = costJ,

x0 = initial_theta,

args = (X,y),

maxiter = 400,

fprime = gradient)

You can see that I’ve specified five keyword arguments. Firstly, in order to use this algorithm in Python (and fminunc in Matlab), you need to provide the function (f) that you are trying to minimise (costJ, which I defined above). You also give the function i) starting values of (x0), ii) additional arguments are taken by your function (args) and iii) the maximum number of iterations that it should perform (maxiter). You can also optionally provide the gradient of the function (fprime), which is its partial derivative. We were already told in our course notes what the partial derivative of our cost function was:

The gradient argument is itself a function for finding that partial derivative of the cost function. Here’s how my code for the gradient term looks in Python:

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

8

9

10

11

def gradient(theta,X,y):

m = len(y)

hypothesis = sigmoid(X.dot(theta).T)

error = hypothesis-y

gradient = []

for i in range(len(X.columns)):

gradient.append(np.sum(error*(X.iloc[:,i]))/m)

gradient = np.asarray(gradient)

return gradient

How the BFGS algorithm actually works is a bit of a black box to me. In the course videos Ng says that we don’t need to know how they work to use them effectively, but I’d still like a broad understanding of what’s going on; maybe I’ll cover this in another post.

The decision boundary

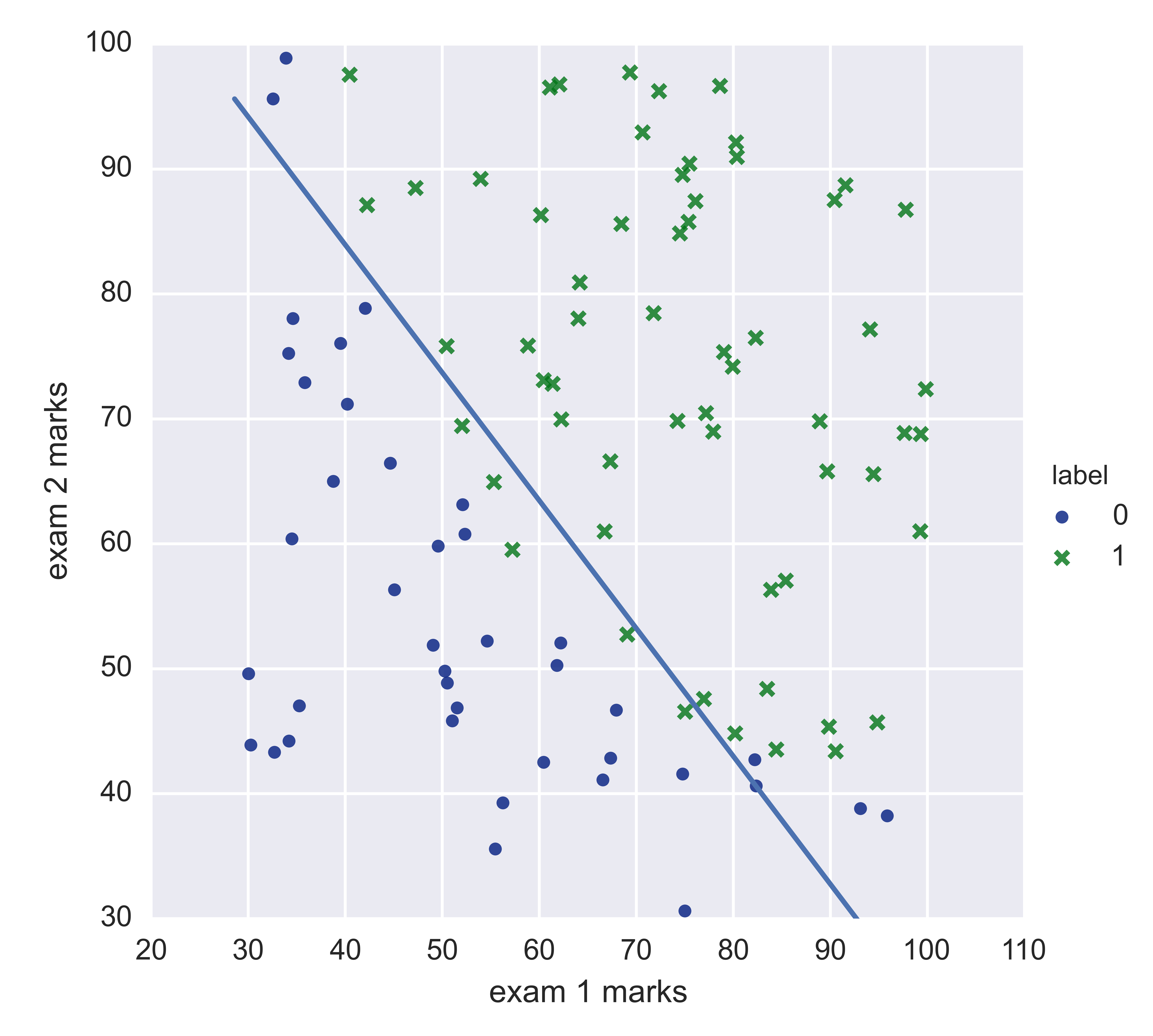

Now that we have a set of values for our parameters \(\theta\) that minimise the cost function, we can plot on our graph of exam scores where the line is that divides students who will be admitted, and those who won’t be admitted, according to our machine learning predictions. This is called the decision boundary. To give you an idea of what a decision boundary looks like, here is the decision boundary for our exam data, plotted using the minimum values of that we got from our BFGS algorithm:

You can see that on our two-dimensional scatter plot, the decision boundary is represented as a line. Any points that fall to the bottom left of the decision boundary are students that will not be admitted to university, whereas those falling to the top right will be admitted. If there was only one input feature, the decision boundary would have been a point, and if there had been three input features it would have been a plane in the three-dimensional space, and so on. We had already been told that our decision boundary would be at \(h_\theta(x) = 0.5\). This means that any values that generates that are greater than or equal to 0.5, we will assign to class 1, in other words we will predict that these students will be admitted to university. The opposite prediction will be made if is less than 0.5 - we predict that these students will be rejected. Remember the probability threshold I mentioned way back at the start of this post, that turns logistic regression into a classification algorithm? This is it.

We can plot the decision boundary by generating values for \(x\) and solving \(h_\theta(x) = 0.5\). The equation we’re using to relate our input features looks like this:

As you can see from the distribution of dots and crosses in our training set compared to the decision boundary in the graph above, our machine learning hypotheses are not 100% accurate. This is not necessarily a bad thing: we don’t want to overfit our data so that it’s no longer generalisable to other datasets. But maybe we could have picked a better function to describe the relationship between exam scores and admittance, for example one that would capture more of a curve to the data. We can work out how accurate our machine learning predictor is by feeding it the original dataset, and then comparing our predicted to the actual results. I defined a function that uses our optimum values of \(\theta\) from the BFGS algorithm to predict whether any given student will get into university or not:

1

2

3

def predict(theta, X):

p_1 = sigmoid(X.dot(theta))

return (p_1 >= 0.5).astype(int)

When we feed this function our training dataset of features (X), and compare the output to the actual outcomes (y), we see (in the ipython notebook again) that our machine learning predictor was accurate 89% of the time.

Unanswered questions I have after week three

There’s still things about this week’s material that I don’t understand. I thought I’d list these here in the hopes that a) they’ll be a reminder to myself to go and find out the answer, and b) if anyone is reading this and can help, they can get in touch.

-

How do you decide what function you will use for your decision boundary? We were told to use a linear function, but maybe a polynomial would have worked better.

-

How do you decide which learning algorithm you’re going to use? Scipy has loads, and I implemented two (BFGS and Newton’s method) with similar results.

-

How do we decide what our threshold value should be for assigning different classes? Maybe 0.5 isn’t always appropriate.

If you made it this far, thanks for reading! My completion of Coursera’s machine learning course might go on to the back burner a bit in coming weeks, as I’m starting S2DS soon which will be a full-time bootcamp. So I’m expecting the next few posts to be about that :)