My summer of data science for social good

14 Jan 2017A happy new year to you for 2017 - here is a long overdue blog update! Almost a year ago now, I wrote a return statement for my time at the Recurse Center. Very belatedly, this is my return statement for DSSG (The Data Science for Social Good Summer Fellowship).

TLDR: It’s not an exaggeration to say that I had one of the best summers of my life at DSSG. If you’re considering whether this is a worthwhile thing to spend three months of your life doing, I say emphatically yes! Applications for summer 2017 are open now until the end of January.

What’s it all about?

DSSG is a programme that trains aspiring data scientists to work on social good problems. Around 45 fellows come to Chicago in the summer for 14 weeks to work in teams and build real data science solutions to problems faced by a range of social organisations. On the face of it, DSSG sounds similar in format to a data science bootcamp like Insight or The Data Incubator to name just two.

There are indeed similarities to a bootcamp: it is a high-intensity environment, there are a lot of people coming from academic backgrounds, and you spend your time working on data science projects. However, it is not a bootcamp as the term is commonly used. Its purpose is not to make money or to land its participants jobs after the summer. The goal of DSSG is to train fellows from academic backgrounds in how to use data science skills (such as statistics, machine learning, data mining etc.) to work on problems of a social nature. A parallel goal is to teach partner organisations in the social good space (such as non-profits or governmental organisations) how to work with data scientists to solve problems.

I will say from my experience having also attended the S2DS bootcamp in London, that DSSG felt completely different. There was a real buzz of excitement in the air from working on meaningful problems. People were having thoughtful conversations about our work and how it fitted into the wider world on a daily basis. We also got to interact with the social organisations themselves, and get a feel for the challenges they face. To put it bluntly, if you’re just looking to find a data science job (and there’s nothing wrong with that) you’re probably better off trying one of the hundreds of bootcamps that already exist. If, however, you have data science skills (and that category has a broad scope) that you want to use for social good, this could be for you.

The project

The view from the DSSG work space in downtown Chicago

The view from the DSSG work space in downtown Chicago

During the fellowship, I worked in a team of four on a project for the Metro Nashville Police Department, creating an early intervention system to predict officers who are at risk of adverse interactions with the public. An adverse interaction could be anything from an injury (to a civilian or officer), a poorly-judged use of force, or a citizen complaint. Such events range in severity, but at their worst they can have tragic and irreparable consequences for the individuals and departments involved.

At the heart of this project was the need to try to predict these types of events before they occur. With this information, departments can intervene (by offering officers extra training, counselling or other interventions) and ideally prevent these negative events from ever occurring at all. With recent events in the states, this is obviously a highly emotionally-charged topic. It was challenging to maintain a balanced perspective for our work, whilst there was (and still continues to be) what felt like real social upheaval happening around us. At times this was difficult to navigate, but it was also an immensely valuable learning experience.

A Black lives matter demonstration I saw on my way home from work. They were happening all over the states whilst I was in Chicago.

A Black lives matter demonstration I saw on my way home from work. They were happening all over the states whilst I was in Chicago.

The data

We had access to 5 years’ worth of internal data from the police department, including information about the characteristics of individual officers (age, gender etc.), the districts they worked in, any activity they had participated in (such as when and where they were dispatched to) and any complaints filed against them, or compliments they had received. We used individual officers that had been involved in an adverse incident as our labelled data (the thing we were trying to predict and prevent).

We created a pipeline to clean the data, format it, run machine learning models on it and ultimately create a risk score for each officer. This risk score was a prediction for how likely an officer was to have an adverse interaction in the next year. In order to check the success of our predictions, we used a method called temporal cross-validation (otherwise known as ‘rolling forecasting origin’) which involved picking a day in the past, training the model using data up until that point, and then testing whether the model could predict what would happen in the ‘future’ (the remaining data we had).

Project collaboration and designing a database

Our project was actually a continuation of a project that was initiated in Charlotte, NC last year. The Charlotte project was also being continued by another team of fellows this year and so we worked in close collaboration with them, since our projects were so similar.

So similar, in fact, that we built a single pipeline that both of us used to create our officer risk scores. During the summer I guest blogged for DSSG about the process of creating a common database schema to house data from both Nashville and Charlotte’s police departments. It was really interesting to sit down and design a database schema and pipeline process from scratch. What is great about working on early-stage projects like these is how much input we each got to have over the design process.

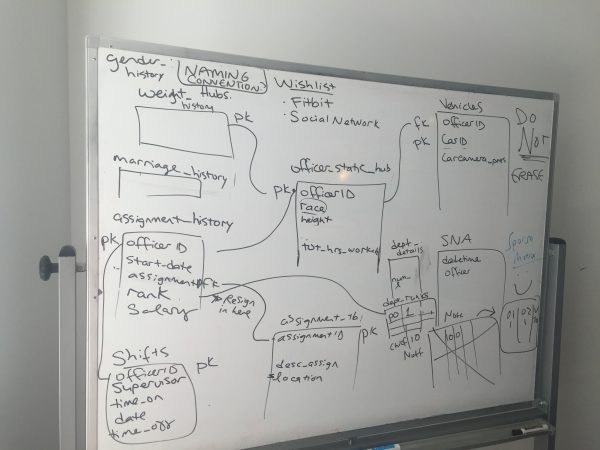

One of many whiteboards we used to design our database

One of many whiteboards we used to design our database

Feature generation

Aside from ETL (Extract, Transform, Load), a lot of our time was spent generating features. This is where our weekly meetings and the site visit to Nashville (you can read about the site visit that the Charlotte team went on) became so useful. The knowledge of the police officers was incredibly informative in telling us what features could turn out to be predictive. For example: one warning sign they suggested for an officer under stress is someone who is taking a lot of days off after their regular days off; this could be indicative of someone with a substance abuse problem. Similarly, an officer who is going through a divorce is likely to be under a lot more stress than usual. Working on this project, it was clear that a successful outcome was going to involve constant communication and feedback between us and our project partners in Nashville.

The results

By the end of the summer, our top-performing model (a variation on a Random Forest) was able to correctly flag 80% of officers who would go on to have an adverse interaction, whilst only requiring intervention on 30% of officers in order to do so. Although this was just a first pass, if we had been using a threshold-based system as has been used in other police departments, we would have needed to flag 2 out of every 3 police officers in the department for the same level of accuracy. The Center for Data Science and Public Policy continues to carry this project forward, and the intention is that it will soon be implemented in real life. The code that we wrote will also soon be made open source. You can read an official update on the police projects from this summer on the DSSG website.

The people

I’ve talked a lot about the project, but for me DSSG was really all about the people. The people were so great. It can be hard as an adult to make real and lasting friendships; DSSG was a wonderful exception to that rule. I found myself making real connections, quickly. Everyone was smart, engaged, and cared about the world. After the three months were over, it felt like we’d known each other a lot longer. The best way I can describe it is that it was like being at summer camp for adults. I’m looking forward to seeing what this community will go on to do in the coming years.

Summary

DSSG exceeded my expectations. I got to learn from and interact with a community of people who care about using their skills to do social good, some of whom I expect to be friends with for life. The project itself was exciting and I learned a lot about what it takes to work with data science on social problems (hint: it’s not straightforward!). We were also given loads of opportunities to present our work to the other fellows and at meetups with the local tech community. The outcome of the projects themselves was only one small part the wider goal of training and education. As far as making an impact is concerned, DSSG is playing the long game.