Week 5 - Python, Pairing, Planigale

12 Dec 2015Last week was my most productive so far at RC, both in terms of outputs and in terms of learning. I decided I wanted a break from Twitter, and so I paired all week with Dave on a matching game in Python. The original aim was to practice and get better at Python, but along the way we’ve also learned about APIs, object-oriented programming, git workflows and Flask apps. I’ll highlight in this blog post whenever I’m talking about a concept that was new to me personally.

Game concept

The game concept is pretty simple: have a picture of something, with three words listed underneath, only one of which relates to the thing in the picture. Pick the correct word.

The ‘somethings’ in question here are animals, plants or fungi taken from the Encyclopedia of Life (EOL) database. The EOL is an online repository of all of the species known to mankind, and they have an API with which to grab their data. Each organism has its own page with information about it including pictures. We spent the best part of a day and a half working out how to access the data and put it into a Python object (which we called Species). This involved working out how to read in and navigate the JSON object returned from the API. In the end, we chose to use 500 species from the EOL hotlist collection, sorted by ‘richness’ (a measure of how complete the records are). We only wanted the species with more information, as these were more likely to have pictures. We gave these Species objects self.scientific_name, self.common_name and self.images_list attributes.

We called our game Planigale after the smallest marsupial species. It’s a cute but vicious creature that fits on the top of your thumb.

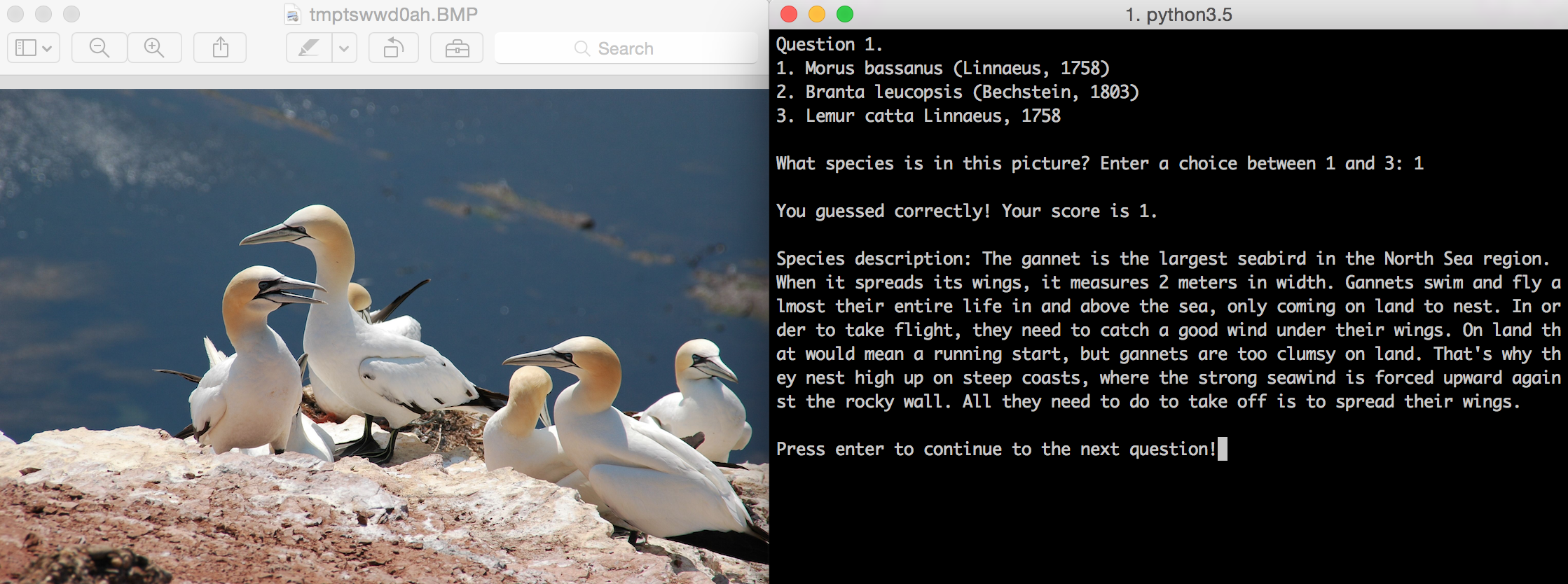

Planigale v1.0: in the terminal

Our first iteration of the game is played in the terminal. We used an object-oriented approach, and in addition to our species object, we made objects for the Questions (containing the information about the species in each question, and which one is the correct answer) and the Games (containing attributes like score and number of questions, as well as functions for game play, displaying questions, getting guesses and displaying the final score). We figured out a way to make the pictures pop up in a separate window, using the pillow library.

Learning point: if __name__ == '__main__'

Everything in Python is an object, including modules. All modules have a built-in attribute called __name__. When you import a module __name__ is default set to the name of the module. However, if you’re running the module directly, __name__ is set to '__main__'. if __name__ == '__main__' allows you to specify which code should only run when your file is run as a script, as opposed to imported as a module.

Learning point: Python pickles

Python has a whimsically-named module for serialising Python objects (this just means converting them into a format that can be stored), called pickle. Pickles allow you to save Python objects from your session and retrieve them very quickly in a later session. In our case, running the script to grab 500 pages from the EOL API and transform this into Python Species objects took a really long time (several hours on the first go). Saving the list of Species objects in a pickle file in the same directory as the game means that loading the data in a future session is the work of moments.

Learning point: Python decorators

Much of this week was spent learning about Python innards. I have found this super fascinating, having used the language for a while without a clear idea of what was going on sometimes. Dave and Ezekiel ran a session about Python generators and iterators, which was illuminating. One Python goodie I had never come across before are decorators. Decorators are syntactic sugar for a wrapper, a function that takes another function as an argument, modifies it, and returns a modified function. In Python, these start with an @ symbol. A couple of decorators that we used in Planigale were @staticmethod and @classmethod. These are built-in decorators; you don’t need to define them anywhere. Functions defined within @staticmethod act like normal functions, except you can call them from within the instance or class. @staticmethod is used to group together group functions that have some logical connection to a class.

Conversely, @classmethod implicitly takes the object instance as the first argument. This way, the method will always be bound to the class it was born in. Any subclasses defined that inherit from this class will also inherit this method and it will keep working. You might use @classmethod to make an alternative constructor for your class. For example, normally our Species class needs lots of arguments like scientific_name, common_name, images_list etc. to instantiate. However, using an @class_method to wrap a from_eolid function that just takes the ID of the species in question, and then goes and finds out all of this other information itself, and then instantiates the Species object using it. Better explanations with code here.

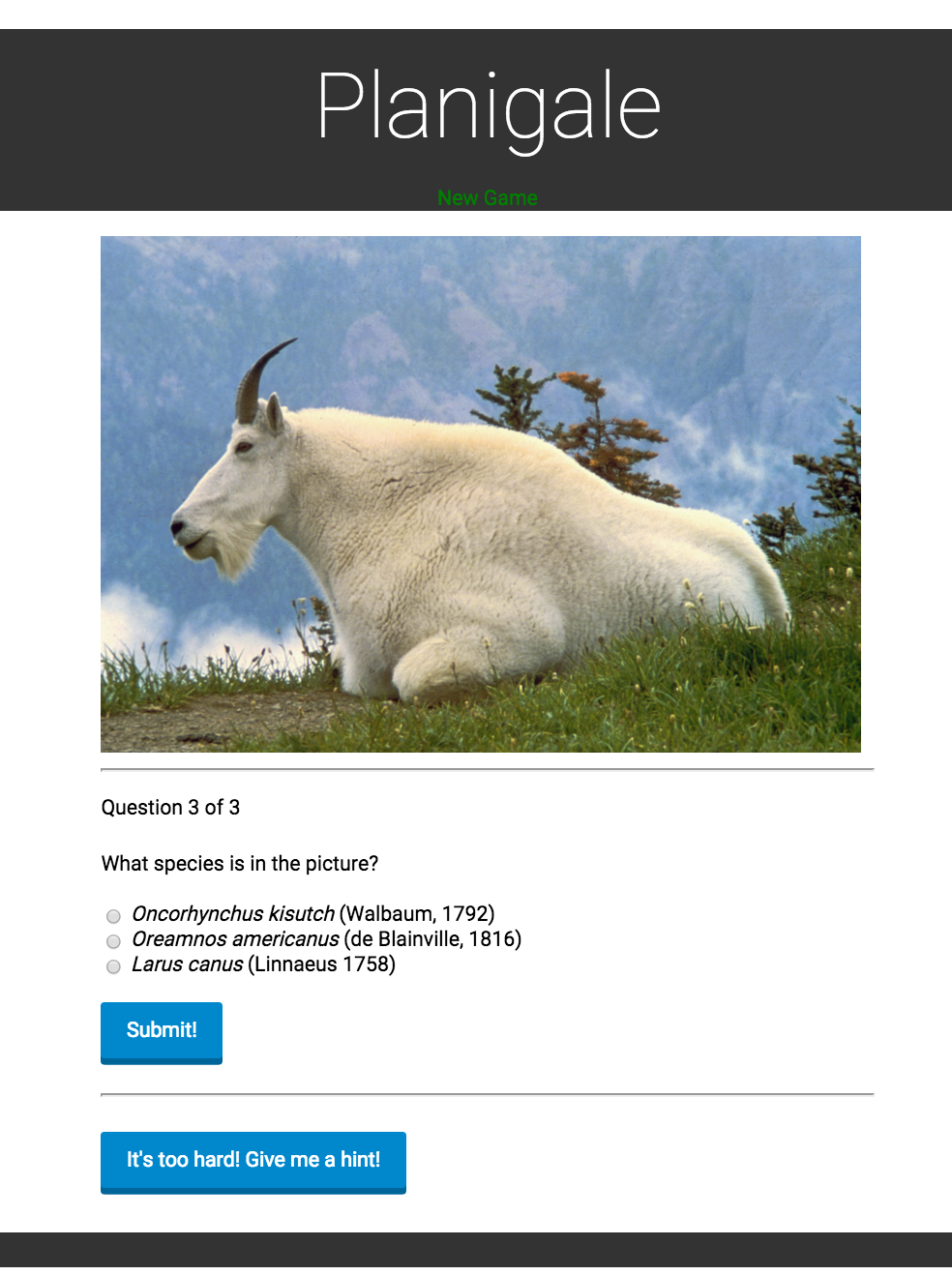

Planigale v2.0: Flask app

We wanted to make our game easily sharable and playable by people without having to use the command line, so our next iteration was a Flask app. Flask is a Python framework for building web apps. It’s similar to Django, but is simpler. I haven’t read extensively about Flask, but here’s the perspective I have as a first time user: Flask doesn’t magically make web pages for you (sadface). What it does is it simplifies the process of doing things that web applications need to do, which you would otherwise be doing by hand.

In our case, we imported a bunch of objects from the Flask module (these are things like request and session). We built a really simple web page with HTML and CSS. Then we used special syntax that Flask and its associated dependencies (Jinja2 and Werkzeug) to pass information between the web page in the browser and our back-end python script with each HTTP request.

Learning point: HTTP requests

The more I learn about web development, the more I realise how it’s all just devil magic to me, and there’s a whole world of stuff there that I have NO IDEA about. On such thing was HTTP requests. HTTP stands for ‘Hypertext Transfer Protocol’, which is a set of rules for how information across the web. When the browser wants to get information from or sends information to the server, it sends an HTTP request using one of several methods that describes the desired action, e.g. GET (for retrieving data from the server) and POST (for sending data from the browser to the server). Flask listens for requests from particular URLs using the route() decorator (yay decorators!). The function inside the decorator generates URLs using information that we pass to it. A simple example looks like this (from the Flask documentation):

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

8

9

from flask import Flask

app = Flask(__name__)

@app.route('/')

def hello_world():

return 'Hello World!'

if __name__ == '__main__':

app.run()

The goal for this week is to get the app finished and hosted on Heroku. Currently we’re deep in CSS layout woes. Another blog post, perhaps.